Effective immediately, this blog is being subsumed into my other, The Buddhist Books Blog.

On reading Buddhist books

I’m now on to my second book about the paramis (Skt paramitas) and I’ve come to a conclusion: what people read, what sells, and what has lasting value can be divided into three types of literature or writing. These are…

Wait! First, I want to preface my pending revelation with a rather obvious statement: This is just my opinion. Nobody should get offended or think I’m talking down to them. I am a certain type of person and as such have certain preferences and standards. What works for me is not what’s going to work for everyone–if I have gained one iota of wisdom in my nearly half century of living, this much at least I can be sure of. Now, back to the revelation.

The three types of Buddhist literature are:

Popular: This type of book sells surprisingly well and is always twice as long as it needs to be. For better or worse, a lot of people who aren’t even Buddhist read this stuff and feel good about themselves on account of reading it. As a result, you definitely know who the authors of these books are so I won’t bother telling you their names.

Now, here’s how you can tell a Buddhist book is a “popular” book.

- If you do an Amazon search for “Buddhism” it probably comes up near the top of the list.

- The author was once a monk or nun but realized at some point that writing books was a more lucrative endeavor.

- The author is now a media personality and has founded one or more organizations.

- The author quotes indiscriminately from all the different Buddhist schools–as well as from Christian, Jewish, Hindu, Taoist, secular, and scientific writers, maybe even popular songs.

- The word “being” is used at least once every other page of every book the author writes.

- Quotes from other people and books are never given more attribution than the fact they were said/written by so-and-so. In other words, the source text is rarely cited, and chapter and verse are never offered.

- Quotes from the Buddha, especially, sound like someone talking at your office–with an amazingly modern diction and vocabulary for a guy who died two and a half millennia ago. Again, chapter and verse are nowhere to be seen.

- The historical veracity of the Mahayana and Vajrayana accounts of the Buddha’s words and biography are never doubted.

- The ultimate truth and unity of all religions is not questioned.

- Mother Theresa and/or Martin Luther King will be mentioned at least once and their sublime virtues discussed in passing

- Everyone is naturally, originally, uniquely, perfectly Good–if only they knew it.

- The writer’s grandmother was invariably the wisest and most awesome of hidden sages.

- There are no footnotes, endnotes or bibliography, and indexes are optional.

- The titles of these books are often derived from well known sayings, songs, or folksy expressions, etc.

Scholarly/practical: The authors of these sorts of books often have significant contemplative experience under their belts, with academic training to boot, though some are purely academic in their background and just happened to have broken into the public consciousness. While not usually as popular or well known as the writers of “popular” books, their work can sell well. Authors I would put in this category include Walpola Rahula (What the Buddha Taught), Gil Fronsdal (translator of the Dhammapada), Bhikkhu Bodhi, Daniel Goleman, and Henepola Gunaratna (Mindfulness In Plain English). Their works are typically characterized by the following:

- 80-90% less fluff language than is found in the works of popular writers; instead, their language is typically crisp and intelligent though not dry or opaque.

- Uncommon and unique insights–no garden variety “wisdom” here.

- Almost always include indexes, as well as–frequently–bibliographies and endnotes.

- They actually provide citations for quotes and don’t rephrase the quotes to make them sound like 21st century utterances.

- Fewer stories from regular life, though these are still included. Instead, many more stories and examples from original sources.

- You probably won’t learn anything about their grandmother, cat, or best friend.

- They are mindful of the differences between Buddhist schools and, except on rare occasions, don’t feel the need to invite comparisons with other religions and philosophies.

- You are more likely to remember one of these books a year later than you are a popular book.

- You are more likely to keep one of these books with the intention of rereading or consulting it in the future than you are a popular work, which will probably turn yellow on your shelf, assuming you don’t first charitably donate it to your local library or regift it to a wayward relative.

- You will probably want to underline, highlight or otherwise mark up one of these books.

- The authors of these books are less prolific than popular writers. So the book in your hand will probably be one of only two or three (max) widely known works by him or her. Popular writers, on the other hand, are constantly coming out with new and improved versions of the Dharma they wrote about last year.

Scholarly: These books are easily spotted. They usually come from university presses and you have to dig for them on Amazon. Their authors are invariably professors, scholars, and other learned sorts–or were: maybe now they are living out a hermit-like retirement. While some of these authors are good writers, they don’t hesitate knocking you over the head with Pali, Sanskrit, Tibetan, Chinese, Japanese and/or Korean technical terms, and their sentences can take on a cerebral knottiness that requires multiple reads. (Note: Tibetan terms in these books are invariably rendered in English via the unpronounceable Wylie system.) Furthermore:

- Diacritic marks and the italicization of technical terms are inevitable.

- Endnotes can run for dozens of pages.

- There is often a bibliography of works from the original language (Sanskrit, Chinese, etc).

- You have never heard of the author apart from the book in your hands.

- He or she may or may not be Buddhist. If the author is Buddhist, he or she has not informed any professional colleagues about this fact.

- The author probably doesn’t meditate because that would (allegedly) impair his or her objectivity.

- The book may never break out of hardback and will be three times more expensive than a regular book of the same size and make.

- The topic of the book will be about a particular doctrine of a particular school in a particular century that ended long before you or anyone you know ever breathed.

- You will feel very intelligent while reading the book, but afterwards you will wonder what you should do with all that knowledge.

- You will probably keep the book, but will be afraid to open it again.

- No more than one–maybe two–people will have reviewed the book on Amazon.

- The reviewers’ comments will indicate they are much smarter and better read than you are.

I have read many examples of all three. Popular books occasionally contain gems scattered among the endless deserts of vapid prose. This, and the inevitable language of optimistic self-improvement they employ (hence the fluffy verbiage), is what keeps you reading them–they tell you you’re extraordinary, that you possess Buddha-nature (if only you could see it!), and you want to believe, so you read and read and read and read. If you’re a beginner, these are naturally the sorts of books you’ll start with, but if you don’t get beyond them you’re probably doomed to never learn anything you couldn’t have gleaned from the pages of Reader’s Digest.

Most of the best reading you’ll do will be by scholar-practitioners. These people really have something to say. They’re not looking for the next big seller; they know what meditation is about; they don’t have an organization to support; and they’ve done some hard scholarly work so they’re familiar with the original texts and the histories. Read as many of these books as you can, but when particular issues become problematic for you or whet your interest, don’t be afraid of good scholars and their tomes, however heavy. Some examples of excellent scholars and their work would be Selfless Persons by Steve Collins, books by Richard Gombrich and Paul Williams, David Loy (Nonduality and others) and Early Buddhism: A New Approach by Sue Hamilton-Blyth among many, many others.

Happy reading!

Bodhiwhatsa?

Incidentally, in any Middle Indo-Aryan language, the word would be bodhisatta. This was Sanskritized as bodhisattva, “enlightenment being,” and we take this meaning for granted; but the Sanskritized form might be wrong. For MIA bodhisatta could also represent Sanskrit bodhisakta, meaning “one intent on enlightenment,” “one devoted to enlightenment,” and this makes better sense than “an enlightenment being.” –Bhikkhu Bodhi, “Arahants, Bodhisattvas, and Buddhas” fn. 3

I only recently read this excellent essay by Bhikkhu Bodhi, and the little endnoted tidbit quoted above got me thinking. I’d encountered similar speculation before but this time, given my current program of reading and interests, it especially struck a chord. So, what indeed is the proper interpretation of this word when rendered in Sanskrit?

Not being a Sanskrit scholar, I have little to go on. But wait! There is this omniscient source of knowledge we 21st century folk have on hand, and it is called “Google”! I shall ask the almighty Google and see what It has to say.

Actually, before we get to what Google knows, I’d like to say what I know. Bodhi is a noun form in Pali and Sanskrit derived from the verb budh “to awake” or “to understand.” Often translated as “enlightenment,” “awakening” is the translation best in keeping with the word’s etymology and intent. Sattva (or satta in Pali) denotes a “living being” or, simply, “being,” coming from the root form sat (as in satcitānanda), in turn derived from the verbal form for “to be.” The English equivalents seem to have exactly followed Sanskrit usage and derivation: to be–>being–>living being. So, bodhisattva means “awakening being.”

Or does it?

The first Google source I happened upon (aside from Bhikkhu Bodhi’s quote above) concerning this issue came from the excellent Jayarava’s Raves blog. Jayarava is a member of the Triratna Buddhist Order and a self-proclaimed autodidact (seems only fitting) who writes on “etymology and the history of language; textual interpretation and criticism, especially the Pāli suttas; the history of ancient India, and particularly the history of ideas with respect to Buddhism; and the integration of Buddhism with contemporary Western Culture, with an emphasis on science.” All of this is wonderful stuff, and perfectly suited for our present inquiry.

Jayarava has this to say about possible origins of the Sanskrit word sattva:

It’s plausible enough, however the Pāli commentaries take the Pāli equivalent satta as related to either sakta ‘intent on’ (the past-participle of the verb √sañj ‘clinging’); or from śakta meaning ‘capable of’ (pp from √śak ‘strong, capable, able’). The suggestion then is that sattva is a hyper-sanskritisation similar to sūkta > sutta >sūtra… In this case Sanskrit satka, śakta and sattva all become satta in Pāli and other Prakrits. The option of ‘intent on’ (satka) would fit the way ‘bodhisattva’ practitioners are described in very early Mahāyāna Sūtras…

The long and short of this seems to be that the Pali satta is multi-valent, and can be feasibly rendered into Sanskrit several ways.

From K.R. Norman’s Buddhist Forum Volume V: Philological Approach to Buddhism, p. 88, we find a similar idea. Norman describes bodhisattva as a “back-formation from Middle Indo-Aryan bodhisatta,” clearly indicating the primacy of the Pali form and opening the door to multiple interpretations and renderings in Sanskrit. He goes on to say that the Pali commentators did not assume the equivalency of satta and sattva. Instead, they offered two derivations:

- from the root sañj- (per Jayarava above) meaning “to be attached to,” which renders in Sanskrit as bodhisakta (I am missing the diacritic under the s), “one attached to bodhi“;

- and from the root śāk, “to be able,” giving bodhiśākta, “one capable of bodhi“.

Judging by the above, the word we ought to have in English then would be bodhishakta, meaning either “one intent upon” or “capable of” awakening, and this is far, far more fitting for the role the word plays in describing someone who is not yet enlightened, but is going that direction, and destined to fulfill his or her aims. Alas, two millennia of tradition mitigate against using this word, though it is so much more powerful and illustrative of what the bodhisattva is all about.

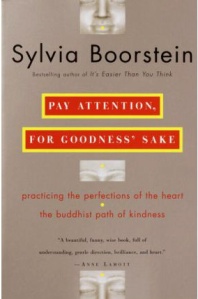

Pay Attention, For Goodness’ Sake by Sylvia Boorstein

Pay Attention, For Goodness’ Sake: practicing the perfections of the heart: the buddhist path of kindness by Sylvia Boorstein. Ballantine Books 2002, 282 pages.

Pay Attention, For Goodness’ Sake: practicing the perfections of the heart: the buddhist path of kindness by Sylvia Boorstein. Ballantine Books 2002, 282 pages.

Boorstein’s book is about the ten paramis (Sanskrit paramitas), written from a Theravadan perspective. She is a practicing psychologist and vipassana teacher, hanging out with folks like Jack Kornfield and Sharon Salzberg. This would seem to stand her in good stead, though I confess I was less than blown away by her book. It had a rambling, chatty, fluffy feeling to it, almost like she sat down at her computer with a cup of coffee and just started writing whatever came to mind. Often the stories she told to illustrate her “points” did not seem particularly connected to the virtue under discussion, be it loving kindness, renunciation, generosity, or whatever. They could go on a bit too–a not particularly illuminating conversation with a cab driver concerning whatever covered three pages (pp. 117-9)! Similarly, the quotes at the heads of the chapters often didn’t seem related to the chapter subject.

The most instructive and original part of her book was the “periodic table of virtue” (pp. 28ff). This was not only insightful but helpful. It reminded me of the table I created off Acariya Dhammapala’s “Treatise on the Paramis” in an earlier post. A few of her stories were also quite good. I especially recommend the one about Bret and his retreat experience (memories of getting mugged) from pp. 236ff, and Boorstein’s musings on her own ten year long grudge against a fellow meditation teacher (168ff). Then there is the hilarious–though totally irrelevant–piece about Seung Sahn and Kalu Rinpoche. I once met the former and am familiar with his book titles, every one of which prefaces his name with the self-styled title “Zen Master.” He never impressed me and Boorstein’s story (on p. 196) not only confirmed my opinion of him but also put me on notice that it really is possible to be too Zen. The story is so priceless I quote it here in full:

Students of the Korean teacher Seung Sahn, the founder of the Providence Zen Center, and students of Kalu Rinpoche, a lama (priest) in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, arranged for the two venerable lineage holders to appear together for a public dialogue. Seung Sahn took an orange out of the sleeve of his robes, held it up for Kalu Rinpoche to see, and said, in the forthright style characteristic of Zen, “What is this?” Kalu Rinpoche’s interpreters translated the question for him, but he seemed mystified. “What is this?” Seung Sahn repeated the question. Still the lama remained mystified. Seung Sahn asked a third time.

Kalu Rinpoche turned to his interpreter and said, “What’s the matter with him? Don’t they have oranges in Korea?”

While I am always happy to be amused, I would have liked more serious practice related suggestions, such as…”here’s a parami, and these are ways you can develop it.” Even when she did attempt “practice points” they were mostly bland mindfulness exercises which, while good in themselves, lacked the specificity to really develop that particular trait. I would have also liked more context. As noted, this book is about the paramis from a Theravadan perspective so, perhaps stereotypically, there was no discussion of the bodhisattva’s career–Acariya Dhammapala and his like are totally absent. While I won’t hold that against Boorstein, in the Theravada the paramis are traditionally associated with particular Jataka stories and the use of some of these as illustrations of the different virtues would have added greatly.

This brings me to what may be the most distressing aspect of the book: the lack of a goal for these practices. I mean, why should anyone bother? Why be generous? Why give up your pleasures, venial or otherwise? This we are never told. The reason, I think, we are never told is because the version of the Buddha’s teaching that comes through in these pages is hopelessly watered down. For example, when Boorstein discusses the Four Noble Truths (pp. 15ff), the third is reduced to simply having a “peaceful mind.” Well, this could mean anything, from post coital slumber to sharing a Bud Lite with your friends on the beach. Another example of this sort of bland evasion of the Dharma’s edgy nuts and bolts is her rendition of the third of the the three marks of existence (annicca, dukkha, anatta), usually translated as not-self or impersonality. Boorstein describes it this way (p. 112):

Nothing has a substantive existence separate from everything else, or indeed any existence at all apart from contingency, apart from being the result of complex causes and a factor in subsequent experience (insight into interdependence).

Huh? Why, I wonder, would she want to make something simple and profound into something vague and garrulous? It seems she is trying to straddle Mahayana and Theravada chairs and falling down between them. In the process, the teaching of anatta is obscured and the third noble truth–the point of the whole enterprise–remains unillumined.

Why? I ask again. Well, I think what we have here is an example of the muddiness of what David Chapman has called “consensus Buddhism“–that is the impetus in certain quarters to take the various Buddhist schools, with all their nuances, contradictions and specific flavors, stick them in a blender, and puree them to a bland mixture that we all have to agree is something called “Buddhism” on account of the lack of a better term. The resulting concoction appeals to the masses but doesn’t say much of anything very well. This is a whole topic unto itself, and Chapman has really run with the ball on this. I suggest spending time on his sites to see what it’s all about. For here and now, though, I will only point out that what consensus Buddhism can never offer is an intellectually challenging platform for practice because that might make some people uncomfortable.

This is not a bad book, but it is by no means great, either, despite all the gushing recommendations from Boorstein’s fellow Dharma teachers. If you are earnestly inquiring into the bodhisattva project I would suggest you pass on it.

My Amazon rating: 3 stars

Technical difficulties for the bodhisattva

For anyone interested in the bodhisattva project, the historic contention between the Theravada on the one hand and the Mahayana/Vajrayana on the other cannot be overlooked. While the Theravada, it is assumed, champions the arahant, the later Buddhist traditions champion the bodhisattva, and the line of conflict between these camps has been drawn about there. But this is in fact a facile, not to mention fatuous, division, as I have personally known Theravadan (allegedly “hinayana”) monks who had themselves made determinations to become a buddha. For example, the late Venerable Panaduwa Khemananda of Nissarana Vanaya in Sri Lanka was known by his pupils to have practiced insight meditation many times to the level of equanimity, but always stopping short of stream entry so he might delay his enlightenment and allow continued development of the paramis and other requisites of enlightenment. (He was the abbot when I resided in the hermitage back in 1994—a very sweet man who often expressed sympathy for me and my gastric troubles as he himself was no stranger to chronic stomach problems.) I also met other Sinhalese monks who were dedicated entirely to metta-bhavana for the purpose of better expressing compassion in this and future lives. And, of course, as anyone who’s read my earlier posts knows, the Acariya Dhammapala authored an early treatise on the paramis for the purpose of attaining buddhahood, and did so expressly on the authority of the Pali Canon. So, the bodhisattva project is well-known in the Theravada school, and there are those who live and practice with its goal in mind.

On exactly this subject Bhikkhu Bodhi has authored a wonderful essay which I would urge everyone to read. It can be found here. There is only one point I would like to add to it:

Something that is either not understood or simply unknown in Mahayana/Vajrayana circles is that if a practitioner wants to become a buddha, he or she cannot, in this current life, gain any of the paths. That is, they cannot experience “cessation” (nirodha), meaning nirvana. The reason is that per virtually all sources available, both canonical and modern day first-hand accounts, once one attains at least first path (“stream entry”), the process of enlightenment begins unfolding ineluctably. It may proceed quickly or slowly, but a self-evolving process gets started that continues whether one practices meditation or not.

Canonical accounts say that no more than seven lives remain for the stream enterer. Whether this is the case or not I have no way of knowing (I’m always suspicious of any occult or spiritual phenomenon based on the number seven), but the general import, I think it safe to say, is that stream entry guarantees very few lives remaining to be born, develop paramis, die, then do more of the same. The assumption then is that it is highly unlikely the stream enterer next door will be at a level to qualify as a buddha anytime soon, to have developed the psychic faculties and teaching capacities that make a buddha.

The upshot of the above is that all those great Mahayana and Vajrayana practitioners whose enlightenments we are oh so certain of—the Milarepas, Nagarjunas, Huinengs, and Dogens—either weren’t enlightened (since they were holding off until the day of their final buddhahood) or weren’t bodhisattvas. If they got enlightened in the lives for which we know them, they’re over and done, or damn near to it. What we have from them is probably all we’re going to get and we’ll have to wait for someone else to come along to the job of becoming a buddha.

I’ve already mentioned him in a previous post, but I’ll mention him again: Venerable Hsuan-hua, the great Chinese monk who founded City of 10,000 Buddhas, was an avowed bodhisattva. He even vowed not to get enlightened until he could carry myriads of other beings with him! Does that mean he never even got to stream entry? Possibly. Spiritual power (bala in Pali) can manifest in so many ways—hands on healing, shaktipat, clairvoyance, unflagging energy, etc—and a bodhisattva could (indeed should) cultivate all of them, and none of them require supramundane attainments. An intelligent person, accomplishing all this, could also through meditation and reflection come to sufficient understanding of the Dharma that he or she might also be able to teach and guide others into the Stream.

The Mahayana camp needs to acknowledge this technical aspect of the bodhisattva path: no bodhisattva has any Path attainment (i.e. enlightenment) until the day he or she becomes a buddha. S/he may manifest all sorts of powers in the interim, may do any number of great deeds, but the attainment of nirvana has to wait until the last life, the cope stone atop the bodhisattva’s career.

Note: all of the above assumes the reality of rebirth. If rebirth is not a fact in some way or another, then the whole concept of the bodhisattva can never be anything more than a figurative “truth”—we would all be better off getting the path as quick as we can. That much, at least, we know is real.

To do and not to do: Bodhisattva virtue in action

Continuing comments on Acariya Dhammapala’s “A Treatise on the Paramis” (5)

“Virtue,” Acariya Dhammapala tells us, “is twofold as avoidance (varitta) and performance (caritta)” (p. 41). If you keep the five precepts, you are avoiding certain actions. You are not killing, not stealing, not committing adultery, not lying and not using intoxicants. This is a type of virtue, certainly–we might even say a negative virtue. In this way, your goodness is measured by absence.

In the Pali Nikayas this is considered sufficient for the attainment of arhantship. A person not engaging in certain behaviors will remove him or herself from those situations and consequences that ruffle the mind and lead to unfortunate outcomes. For the establishment of a peaceful mind, a mind that is ready to meditate, this is enough.

But here, perhaps, we really do see a difference between the bodhisattva ideal and the ideal of someone who simply wants to meditate for his own well-being. The bodhisattva cannot stand on negative virtue alone, he must go further and act, positively, outwardly, to express compassion to the best of his ability. Virtue must not only be absence, but performance. The bodhisattva must do something.

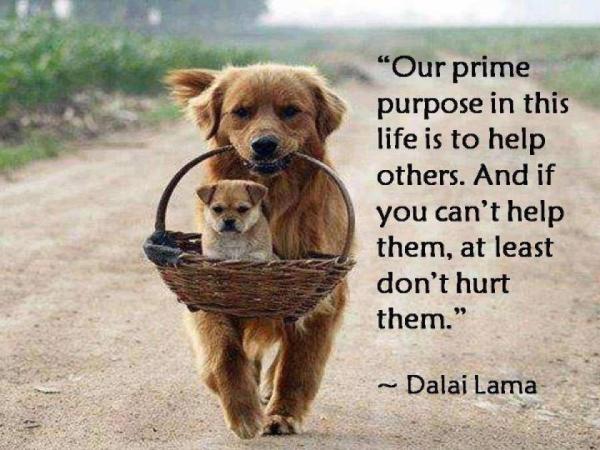

The Dalai Lama’s quote above perfectly captures these two facets of virtue or goodness. At least don’t hurt others (or yourself); that is the lowest standard one should hold oneself to. Going beyond that, practice the opposites of those behaviors the precepts guard against. So, we might say:

- At least, do not kill. Better yet, protect and render assistance to others.

- At least, do not steal. Better yet, give to others (dana).

- At least, don’t misuse your sexual energy. Better yet, be chaste and educate people on the right uses of sexuality (when and as appropriate).

- At least, don’t lie. Better yet, disclose your faults and when you speak, be gentle and informative.

- At least, don’t take intoxicants. Better yet, nourish yourself with healthy, edifying food, what the Hindus call sattvic.

Dhammapala goes into considerable detail about the do’s and dont’s of bodhisattva virtue. Here is my boiled-down version of his virtue as avoidance:

- hold no resentment against anyone

- do not take what is not given

- never arouse a thought of lust for the wives/husbands of others (if a householder)

- abstain from all forms of sexuality (if a renunciate)

- do not say anything untrue, hurtful, unwise, or untimely

- abstain from harsh speech

- abstain from slander

- abstain from idle chatter

- abstain from covetousness, ill will and perverted views

- never injure another

- do no evil deed even if threatened with death

- do not indulge in omens and superstitious practices

- do not indulge in the “diversity of outside creeds”

- abstain from all wrong means of livelihood

- never arouse unwholesome states in others

- never place oneself in a higher position or rank than those who are of inferior conduct

- be neither too accessible nor inaccessible (i.e. associate with others at the proper time)

- do not criticize those who are dear to others in front of them nor praise those who are resented by them

- do not engage in persuasion

- do not accept excessive favors

- do not refuse a proper invitation

Now for virtue as performance:

- speak only truthful, beneficial, endearing, measured and timely talk, especially talk concerned with Dhamma

- possess knowledge of and faith in cause-and-effect

- have faith and respect for recluses who have gone forth and are practicing in the right way

- perfect the practice of loving-kindness

- eradicate hatred, ill-will and aversion

- be devoted to renunciation

- have faith in the enlightenment of the Tathagatas

- treat others with respect and courtesy

- wait upon the sick

- render service to those who ask

- give thanks to those who commend you

- praise the noble qualities of the virtuous

- patiently endure the abuse of antagonists

- always repay help and advice rendered to you

- diligently practice wholesome states of mind

- acknowledge all transgressions and reveal your faults

- do good deeds anonymously [per Dogen]

- dedicate your every goodness to supreme enlightenment

- be a companion to those who need companionship

- comfort and aid the sick and needy

- console the bereaved

- restrain with Dhamma those who need to be restrained

- inspire with Dhamma those who need inspiration

- determine to perform the “loftiest, most difficult, inconceivably powerful deeds of the great bodhisattvas of the past”

- conceal your virtues

- do not become complacent over minor achievements, but strive for successively higher achievements

- assist those who suffer from blindness, deafness and physical disability

- help the faithless gain faith, the lazy generate zeal, the confused develop mindfulness, the unconcentrated gain concentration

- dispel the five hindrances from those who suffer them

- establish beings in wholesome states

All of the above, every last bit of it, is dedicated to the “purpose of becoming an omniscient Buddha in order to enable all beings to acquire the incomparable adornment of virtue” (47). Furthermore:

Thus, esteeming virtue as the foundation for all achievements — as the soil for the origination of all the Buddha-qualities, the beginning, footing, head, and chief of all the qualities issuing in Buddhahood — and recognizing gain, honor, and fame as a foe in the guise of a friend, a bodhisattva should diligently and thoroughly perfect his virtue as a hen guards its eggs: through the power of mindfulness and clear comprehension in the control of bodily and vocal action, in the taming of the sense-faculties, in purification of livelihood, and in the use of the requisites (44).

The Beginning Bodhisattva’s Practice of Virtue

Continuing comments on Acariya Dhammapala’s “A Treatise on the Paramis” (4)

The middle third of Arya Dhammapala’s “A Treatise on the Paramis” is, fittingly, taken up with a discussion of how the paramis are actually practiced (this would be section (x), running from pp. 35-56). Of that chunk, more than half is devoted to the first two paramis, generosity (dana) and virtue (sila). This is not so surprising since they are the foundation for everything else; remember in the suttas the Buddha’s teaching is often explained in brief as dana, sila and bhavana (mental cultivation or meditation).

I think generosity is a pretty easy concept to get–give ’til it hurts, as Mother Teresa said–but virtue, aka morality or ethics, is an entire subject itself, abounding with subtleties and potential complications. So for this post I’d like to discuss Dhammapala’s take on virtue.

Dhammapala tells us virtue is purified by four ways or modes:

- by purifying one’s inclinations, meaning the things that attract or interest you (practicing dhutangas vs watching porn, for example);

- by undertaking precepts;

- by non-transgression, or keeping, of those precepts;

- by making amends (penitence and apologies) for transgressions.

All of these are cultivated, undertaken, encouraged and maintained by a sense of shame over moral transgression (hiri) and moral dread (otappa), which is fear of the results of transgression, and I’d say that it is really these two innate sensibilities that determine, to a greater or lesser degree, how you will behave from an ethical standpoint. On this a lot could be said, but I will note that there are people who possess neither shame nor moral dread, and they are known as sociopaths.

Most of us, fortunately, are not sociopaths. If we break rules or promises (especially those we value), the violation of which lowers us in our own eyes, we feel shame (guilt, too, probably, but there is a difference). We also probably take a quick look around to see if anyone is watching, and, oddly, our relief is not complete even if we’re pretty sure we didn’t get caught. In other words, we fear the consequences that come from breaking trust with others and ourselves–even if the police aren’t going to come get us, the world we know somehow manages to gnaw at our gut.

The important thing is that these tendencies, which in the morally healthy person are strong and quick to come online when needed, can be cultivated, and the four steps above are the process of that cultivation. So what Dhammapala is telling us is that first we must incline toward taking on moral standards, then we must decide to do so, then we have to try to keep the promises we’ve made, and if we don’t….well, we must make it up to someone, as often as not, ourselves.

Precepts are different from commandments. I hope everyone can see this. In Exodus the sky god Yahweh tells his people “You must do this, that and the other thing…or else.” Moses doesn’t stand there and ask why he and the rest have to do all these things–it’s unnerving to have conversations with burning bushes, after all–and Yahweh certainly doesn’t volunteer any justifications: “It’s good for social cohesion,” “You’ll have fewer altercations,” “Your love life will be better,” etc. It’s just a matter of here’s the list, now be obedient.

Notice a commandment is something given without explanation; it’s externally imposed. However, precepts–in Buddhism, at least–are rules of training you take upon yourself because you’ve considered and reflected and come to understand the intelligence behind them. If you have the goal of spiritual awakening, then you will realize that without the guideposts of ethical training rules the chance of you getting to your goal is nil. I’ve written at length elsewhere upon this subject. Here’s a snippet of what I’ve said:

What then is the purpose of ethical behavior? The Buddha discusses this specific question innumerable times throughout the suttas. In brief, one adopts sila (ethical precepts) specifically for the purpose of eliminating mental, verbal and physical actions that give rise to negative mental states, relationships and consequences that hinder mental culture (bhavana). Also, we try to behave generously, graciously, and compassionately because such modes of deportment foster good mental states both within ourselves and others. In other words, depending on what we think, say and do we have the power to increase or decrease suffering in ourselves and others. Since the Buddha’s teaching is concerned entirely with the elimination of suffering (i.e. existential angst), ethical behavior is the bedrock upon which everything else must be built. Without it, the attainment of higher states leading to [nirvana] is out of the question.

Once one understands this, then hiri and otappa come naturally and abundantly and Dhammapala’s four-fold schema follows as a matter of course.

Conditions for Practice of the Paramis

Continuing comments on Acariya Dhammapala’s “A Treatise on the Paramis” (3)

This is my third post commenting on Acariya Dhammapala’s “A Treatise on the Paramis.” In my last post I discussed the aspiration for buddhahood and the daunting list of prerequisites required for it to have any hope of succeeding. But additional to the specific characteristics of the aspirant there are also conditions that must exist for one to even practice the paramis, and I think it’s safe to say these conditions apply whether you really are a bodhisattva or just want to become a better person and/or better spiritual practitioner. So all you regular folks, take note!

Dhammapala writes that three conditions in particular are required just to get the practice of the paramis started. First is the aspiration for buddhahood (or, at a more regular seeming level, the desire for self-improvement), and then great compassion (mahakaruna) and skillful means (upayakosalla). Now at first glance it might seem the aspiration would come first, but a closer look indicates that’s actually not the case. First ask yourself, Why would anyone even make the vow? They would have to be motivated by compassion (big or little), by the desire to help others and to alleviate their suffering. Along with that, they would have to possess the wherewithal, the can-do spirit and facility of skillful means. Merely wanting to help others won’t cut it–without the ability you’ll be ineffectual and probably make a mess of things. On the other hand, ability without interest will result in nothing done. So, one without the other doesn’t work, but when these two exist together, then the determination can be made, so they must precede the aspiration.

But there’s more to it than even that. Dhammapala also mentions four factors, called the “grounds for Buddhahood” (buddhabhumiyo), that need to be present: 1) zeal (ussaha), meaning the energy that strives for the requisites, 2) adroitness (ummanga), which is wisdom in applying skillful means to the requisites, 3) stability (avatthana), or unshakable will for their perfection, and 4) beneficent conduct (hitacariya) which is the development of loving-kindness and compassion.

Honestly, I am doubtful about the usefulness of this list. I think it’s an unnecessary add on, since every one of these is, in some form or another, already a parami. (In other words, I see the paramis as a self-referencing, self-reinforcing system.) When he next adds “six inclinations,” I really feel it’s a bit of Theravadan style list making for the sake of list making. Basically, his idea is you have to be inclined toward the paramis to develop them. Well….duh! Dhammapala also says we should review their opposites to understand the fault of not developing them, and this is certainly a smart mode of reflection to motivate oneself, kind of like reflecting on the merits of fidelity if you imagine yourself getting caught in bed with a paramour! This actually leads to one of the treatise’s meatiest sections, an extended reflection on the positives of parami practice versus the negatives of not practicing. This part of the text, pages 22-33, is really excellent and inspiring reading.

But to get back to the point of this post (which is in danger of getting lost!), on page 33 Dhammapala makes what is certainly the most telling statement in his entire treatise:

Thus one should arouse an especially strong inclination toward promoting the welfare of all beings. And why should loving-kindness be developed toward all beings? Because it is the foundation for compassion. For when one delights in providing for the welfare and happiness of other beings with an unbounded heart, the desire to remove their affliction and suffering becomes powerful and firmly rooted. And compassion is the first of all the qualities issuing in Buddhahood–their footing, foundation, root, head and chief. [emphasis added]

I can’t help but be reminded of Jesus’ saying in Matthew regarding the Biblical Law:

You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind. This is the first and greatest commandment. And a second is like it, You shall love your neighbor as yourself. On these two commandments depend all the law and the prophets.

While I might quibble with his theistic metaphysics, the notion that positive, altruistic motivation should be the inspiration behind all of one’s life is clearly the common thread to the messages of Jesus and the bodhisattva path.

So if we map out the the conditions for the practice of the paramis, and what engenders their development, it might look something like this:

Compassion–>effort–>skillful means (upaya)–>determination–>Aspiration (vow)

Just think of these as baby steps to buddhahood!

The Great Aspiration: Are You Even Qualified to be A Bodhisattva?

Continuing comments on Acariya Dhammapala’s “A Treatise on the Paramis” (2)

In my previous post I left off noting how utterly impossible seeming Dhammapala’s “eight qualifications” for bodhisattvahood were–without actually telling you what those qualifications were! (I didn’t want to depress you any sooner than I had to.) Well, here they are. These are the qualities and characteristics you must possess if your bodhisattva vow has any hope of succeeding:

- A human being (manussatta): You have to be homo sapiens when you make the vow.

- Male sex (lingasampatti): Maybe you can chalk it up to patriarchy, but this is one of the traditional qualifications since, it is assumed, all buddha’s are male. (The Buddha himself is quoted as asserting just this in the Anguttara Nikaya 1.279, on p. 114 of Bhikkhu Bodhi’s translation.) However, the Tibetans–bless their hearts–have a different take on this. According to them there has been at least one female buddha–Lady Tsogyal, consort of Padmasambhava.

- Achievement of the necessary supporting conditions (hetu): Dhammapala does not elaborate on this point, but I think it’s safe to assume it refers to the requisites of enlightenment (bodhisambhara), among which, of course, we can count the paramis.

- Personal presence and sight of the Master (sattharadassana): Here we run into a real problem, since apparently you have to make your vow at the feet of a buddha. Since we know of only one buddha directly and he’s been dead 2,500 years, give or take a century, anyone wanting to make the bodhisattva vow for the first time has already missed their chance. There is still hope, however, and this applies whether you’re currently a man or woman: assuming the truth of rebirth (a big assumption, admittedly, and one I will have to repeatedly make for the purpose of this project) it is possible you did indeed make a vow before Shakyamuni and received his acknowledgment. Even if you are woman now, perhaps you were a man then when you made the vow. After all, the bodhisattva vow is one that must be taken and retaken throughout one’s existence, in succeeding lifetimes, and unless you’ve developed the ability to recall past lives you will not know under what circumstances you previously lived and made the vow. I should point out that while this explanation gets us around the apparent impossibility of this qualification, it does not minimize its difficulty or rarity. (A more optimistic interpretation might say that you could have made the vow at the feet of any buddha, including those previous to Gotama. In which case, with innumerable buddhas and innumerable opportunities, there may in fact be innumerable real McCoy bodhisattvas out there!)

- The going forth (pabbajja): You have to be a homeless renunciate when you make the aspiration, though not necessarily as a bhikkhu in a buddha’s dispensation.

- The achievement of noble qualities (gunasampatti): Not only must you already be a renunciate, but your meditations must have born significant fruit, specifically in the form of jhanas and various psychic powers. The reason for this is that only such a person will have the ability to properly investigate the paramis and understand, on his own, their necessity and nature. So, if you are a bodhisattva and don’t currently manifest these powers, well….something’s gone wrong.

- Extreme dedication (adhikara): The necessity of this trait would seem obvious to the point of being redundant. Honestly, I do not know of any project, task or aim undertaken by persons for their own benefit or the benefit of the world, that is as vast in its stated scope, duration, or challenge as that of the bodhisattva. “World conquest”–the project of Alexanders, Caesars and Napoleons–seems almost a timid affair by comparison.

- Strong desire (chandata): This, too, seems rather obvious. Without a kind of mono-maniacal obsession for spiritual development it hardly seems possible anyone could have a snowball’s chance in Avici hell to attain buddhahood. The aspirant must, as Dhammapala says, possess all the aforesaid qualities and “have strong desire, yearning, and longing to practice the qualities issuing in Buddhahood. Only then does his aspiration succeed, not otherwise.”

Feeling intimidated yet?

Of course, all of this is simply “by the book.” I don’t know where Dhammapala got his information (maybe the devas?) so there is no way to check the veracity of any of it. Also, none of this makes sense if one doesn’t buy into the notion of rebirth; everything is predicated upon the assumption that a vow can carry over from one life to the next.

Stepping back, it’s obvious that if we withhold judgment on whether or not rebirth is true and take the bodhisattva project at its face value, as a soteriology it represents a truly unique culture. There is no other ideology out there where altruism of such a scale is imagined, much less attempted. The fact that there really have been–and are–people who take this aspiration more seriously than anything else and orient their lives, their careers, even their deaths, with this and only this end in mind, is quite staggering if you try to wrap your head around it.

Among modern day practitioners the person whom I think most closely fits the self-consciously lived bodhisattva life is the Venerable Hsuan-hua, one of the two greatest Chinese Ch’an monks of the twentieth century. (The other was his mentor, the Venerable Hsu-yun.) See, here, for example, the vows Hsuan-hua made as a young renunciate. His life, from very early until his death, was marked by a frenzy of teaching activity and the establishment of monasteries, temples and educational and medical facilities, punctuated by sometimes extended periods of intense solitary retreat. Whether or not the intention behind this tremendous labor actually carries over to a new life is not for me to say, but clearly the man’s work and example has had significant ripple effects in the visible world.

Comments on Acariya Dhammapala’s “A Treatise on the Paramis” (1)

This post and several forthcoming will be my thoughts on Acariya Dhammapala’s excellent little “Treatise on the Paramis,” which I’ve now read three times. I don’t have any particular plan or order of progression to follow other than what the text gives, though perhaps some grander, more intelligent approach will reveal itself as I go along.

The paramis as a heuristic tool: Sometime during my second reading I wrote the following at the top of the treatise: “The paramis are a heuristic tool to think about how a person needs to be to 1) best help himself, 2) best help others, 3) perfect samadhi and paññā.” They are a training guide, almost a kind of mnemonic device, for inculcating certain personality traits. As such, they are in no way absolute. That is, the list of ten we have in this treatise could have been twelve or nine or, as they are in the Mahayana tradition, six. This is important to keep in mind, as it will enable one to be flexible in how one appraises one’s own character and tries to effect changes.

The meaning of “parami”: Usually the meaning of the word is given as “perfection,” but Dhammapala offers some interesting wrinkles on this. He says, first, that “bodhisattvas, the great beings, are supreme (parama), since they are the highest of beings by reason of their distinguished qualities…” So the word can also refer to supremacy or primacy. Furthermore, the paramis are the character or conduct of the bodhisattva, of one who is supreme. We could therefore alternately translate the word as “excellence,” so long as we think of excellence in an active sense–as a verb instead of a noun. Thus when you act with excellence or from excellence, you demonstrate the paramis.

Their sequence: In this text and others it’s suggested one performs or perfects the paramis in a sequence. I am not convinced of this. It seems to me the path of development is holistic, with every attribute activating, strengthening and reinforcing, every other one. I’m sure there’s some hard science on this somewhere, but my suspicion is that greater renunciation (self-restraint or discipline) is positively correlated with higher levels of mental energy, or more generally ethical behavior. Some paramis may be easier to perform initially, but that does not mean one will necessarily perfect them in any particular order; this would seem to be determined in great part by native disposition. One should note, too, that throughout the course of the treatise compassion and skillful means are placed first as the guiding lights of all the paramis. They are, in effect, paramis themselves, though not called such. What is compassion but loving-kindness in the general, affective sense, and what is skillful means but wisdom in action? There is lots to say about these categories: how they overlap and interplay, and whether or not this is even the best list. For remember, this is not the only list–the bhumis in Tibetan Buddhism and the Avatamsaka Sutra are different. I’ll need to look at this later, needless to say….

“All the paramis, without exception, have as their characteristic the benefiting of others; as their function, the rendering of help to others, or not vacillating; as their manifestation, the wish for the welfare of others, or Buddhahood; and as their proximate cause, great compassion, or compassion and skillful means.”

Analysis by five ways: The author proceeds to analyze the paramis by five ways. He describes 1) their perfection, or how they ideally manifest; 2) their characteristic, that is what is their fundamental attribute; 3) their function, or what they do; 4) their manifestation, i.e. what do they look like in practice; and 5) their proximate cause, that which allows them to unfold. See the attached table here: The Paramis

The Great Aspiration: Here Dhammapala ramps up the difficulty of the bodhisattva project to inhuman levels. He writes:

The condition of the paramis is, firstly, the great aspiration (abhinihara). This is the aspiration supported by the eight qualifications, which occurs thus: “Crossed I would cross, freed I would free, tamed I would tame, calmed I would calm, comforted I would comfort, attained to nibbana I would lead to nibbana, purified I would purify, enlightened I would enlighten!” This is the condition for all the paramis without exception.

Following this inspiring vow are the “eight qualifications,” and I’m sorry to inform you that none of us, not a single person on the planet, can be certain he or she possesses all eight. To say this is a problem is an understatement, so much so that this section of Dhammapala’s essay is likely to turn people off, depress them, or make them think something’s fishy about the whole thing. However, there is almost assuredly more here than meets the eye, and I do not think we should let ourselves be trapped by tradition–Buddhist or otherwise. My next post will be an essay devoted entirely to the problem of the Great Aspiration and the eight qualifications.